The path/road running South to the River Wear uncovered by the excavations can clearly be seen marked out by the low walls on the right of the picture in the centre.

Professor Dame Rosemary Cramp of Durham University in her excavations of part of what we know to have been the monastic grounds at St. Peter’s between 1963 and 1978 concluded that the pathway that was found to be running down from St. Peter’s to the river Wear pre-dated the monastery.

This then leads us to a question – what had previously been important enough on the site to have it’s own road or pathway? Further archaeology will hopefully provide good evidence of what the site had been. But until that time one other site may provide some indication of what the then King of Northumbria, Oswald, and just as importantly his wife were doing.

A monastery at Lindisfarne (the Parker Chronicle and Peterborough Chronicle annals of AD 793 record an Old English name, Lindisfarena) was founded around AD 634 by the Irish monk Saint Aidan, who had been sent from Iona off the west coast of Scotland to Northumbria at the request of King Oswald. Aidan remained there until his death in 651 but Lindisfarne became the base for Christian evangelism in the North of England and beyond. King Oswald also sent a successful mission headed by Cedd to Mercia which was one of the kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy (a collective name applied to the seven kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon England from the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain in the 5th century until unification into England early in the 10th century). Further monks from the Irish community of Iona settled on the island increasing it’s size. Northumbria’s patron saint, Saint Cuthbert, was a monk and later abbot of the monastery, and his miracles and life are recorded by the Venerable Bede here at St. Peter’s.

Lindisfarne was a school where Anglo-Saxon boys were trained to become priests and missionaries. It was in this school that Cedd and his brothers Caelin, Cynebil and Chad learned to read and write in Latin, and learned to teach the Christian faith to those who could not read Latin.

Cedd’s first mission was to go to the midlands, then called Mercia, at the request of its ruler, King Paeda, who wanted his people to become Christians. Cedd was so successful that when King Sigbert of the East Saxons (Essex) asked for a similar mission, it was Cedd who was sent by King Oswald.

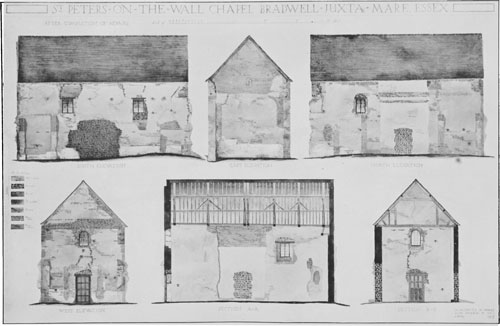

So in 653 Cedd sailed down the east coast of England from Lindisfarne and landed at Bradwell. Cedd found the ruins of a long deserted Roman fort. It is believed he first built a small wooden church to begin his mission. He must have quickly established a congregation because within a year, as there were so many dressed stones from the collapsed Roman fort available, he arranged to create a much more permanent building. Cedd modelled his church on the style of churches in Egypt and Syria. The Celtic Christians were greatly influenced by the churches in that part of the world and we know that St. Antony of Egypt built his church from the ruins of a fort on the banks of a river, just as Cedd did on the banks of the River Blackwater in Essex (then known as the River Pant). This new stone church cathedral was named the St. Peter-on-the-Wall, Bradwell-on-Sea, Essex and was consecrated in AD 654. Cedd’s new Cathedral was built where the gatehouse of the fort had been – as it was built on the wall of the fort so it was named Saint Peter-on-the-Wall. The design of St Peter-on-the-Wall can be seen in the accompanying Plate 36.

An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Essex, Volume 4, South east. Originally published by His Majesty’s Stationery Office, London, 1923.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying and sponsored by English Heritage. All rights reserved.

Cedd died of the plague that ravaged the mainland at that time in AD 664. Shortly after Cedd died, the area of Essex where had built his cathedral in AD 654 was taken into the Diocese of London and St Peter-on-the-Wall became the minster for the surrounding country.

This all gives us a clue as to what was happening at that time at St. Peter’s, Wearmouth under the rule of the King of Northumbria and the royal family. It was a time of profound change as Britain moved inexorably out of the Dark Ages and away from the feuding and barbarism that ensued following the decline and fall of the Roman Empire. Without doubt it was such a successful model for social change that kings asked for it to be used elsewhere. St. Peter’s, Wearmouth that we know today was probably pre-dated by a wooden structure which was built on an established site of importance, quite possibly Roman. Then, just as with St Peter-on-the-Wall, when it had become established replaced by a permanent stone building.